In general, experts have been optimistic that health standards in developing countries will improve. Some have suggested that in 20 years, the infant mortality rate—which is still close to 10% in countries like Somalia, Afghanistan, and Angola—will drop below 2% almost everywhere.

However, in a commentary entitled “Population and climate change: who will the grand convergence leave behind?” published in The Lancet Global Health, a team of UC Berkeley researchers—collaborating with the University of California, San Francisco, Princeton, and the African Institute for Development Policy—warn that unless action is taken, certain countries will likely face dire rates of starvation and disease.

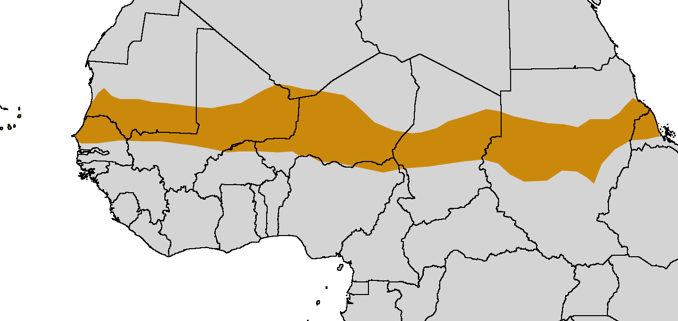

Specifically, they focus on the impacts of a warmer climate in the Sahel—a region with over 100 million that lies between the Sahara desert and Sudanian savanna, stretching from Senegal to Somalia—where temperatures are expected to soar by 9-15 ºF by 2100. This will cause extreme weather events, reduced crop yield, and increased spread of disease by insects. During the same period, the population of the region is predicted to rise to over 600 million.

Of course, this rise in population and temperature will be gradual, and we’re likely to see crises occur well before the year 2100. The temperature is projected to increase by 5-6 degrees by 2050, when the population is already likely to exceed 300 million.

The researchers recommend three measures to prevent impending starvation and disease. One is primarily technological: develop methods to grow drought-resistant crops, prevent pest infestations, improve crop storage, and distribute water more efficiently. “A multidisciplinary approach and a long-term vision are much needed,” the report notes. “Currently many interventions are not adopted until visible water shortages occur.”

Second, international aid must focus more on access to family planning, including reproductive education, contraceptives, and abortion care. This could reduce population growth and thus ameliorate food shortages and the spread of disease.

Third, concerted efforts must be taken to empower and educate women. In the Sahel, child marriage is common. This deprives women of the opportunity to lead autonomous lives—and potentially contribute to economic growth—and leads to pregnancy in immature teens, increasing the odds of mortality and morbidity for both mother and child. The researchers note that programs to educate women have been successful in helping women become leaders of their communities, and parents are often willing to delay their daughters’ marriage in exchange for school fees and books.

“These three key interventions are regarded as mutually supportive,” the researchers explain. “Although they involve long-term considerations, some, such as improved agricultural practices, have immediate payoffs. Programmes need to be integrated so as to exploit intrinsic multiplier effects. For example, educating girls facilitates the adoption of family planning and enhances income generation in the family. Rigorous research and assessment will be essential to build the evidence base for such urgently needed investments. Substantial gaps in demographic, agricultural, and health data need to be filled."

Pursuing any of these measures will require help from governments and international donors, and the researchers advise that these priorities be considered as a framework for aid. "Policies need to be designed to result in measurable, meaningful benefit to the most vulnerable populations," they write. "Interventions must be developed in a human rights framework, ensuring that the benefits do not drift only toward those with the most social and political capital.”

Article Type

- Research Highlights

Add a Comment