Fresh fruit comes with a cost. For many residents of California, this cost is paid at the grocery store, where choice is abundant and prices seem fair. For those who work to supply the fruit we enjoy, the cost is different. The cost is felt. Choices are few, and prices aren’t fair. Migrant farmworkers rise before the sun, labor until dusk, and are paid in miniscule amounts for their heavy labor. The average worker makes $8,000 a year. This labor is hard on workers’ bodies, families, and lives.

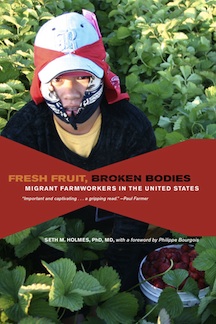

In his book, Fresh Fruit, Broken Bodies (University of California Press, 2013), Seth Holmes, UC Berkeley Professor of Public Health and Medical Anthropology, calls attention to the social and economic structures that produce this inequality, and shows how the suffering of migrant farm-workers is both structural and endemic.

Reflecting on his ethnographic research, which entailed hustling hour after hour across the sun-soaked desert of Northern Mexico in pursuit of the U.S. border, Holmes asks: Is it worth risking your life? Navigating a landscape of inequality, Holmes was held at gunpoint by U.S. Border Patrol agents, arrested, and imprisoned. After spending time in jail with his friends and fellow fieldworkers, he labored in the berry fields of California and Washington State.

As an anthropologist and physician, Holmes represents the promise of cross-disciplinary inquiry that takes seriously the problems of social inequality and risk. His work presents critical perspectives about political and economic structures that separate the United States and Mexico, including how the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has recast and exacerbated economic inequality, leaving native farmers of Mexico little choice but to cross the border. Holmes details how these inequalities are felt in the everyday lives of migrants, and how they produce conditions of medical and social concern.

This inequality continues on the fields where berries are picked, where there is frequently discrimination by farm managers, who give assignments based on race, ethnicity, and skin color. The darker skinned laborers of Oaxaca frequently field racial slurs, and are identified as fit for bent-over picking because they are “closer to the ground,” while other groups rank higher in the labor chain, and are afforded work breaks because their bodies are different. For many, these prejudices result in great strain, repetitive motion, and injury.

By bringing attention to the details of everyday life among a group of people who are native to southern Mexico and have been forced to migrate to the United States and work for very little pay, Holmes shows us how risk is felt personally, inflicts injury, perpetuates hardship, and is structurally produced.

Holmes observes how, because of his tall, bald-headed, white, male body, he is treated differently than others. For those with whom he travels, the risks—of not making enough money to survive, becoming injured, or not making it to the United States—are all compounded by the prejudices of having darker skin, a smaller stature, and a different heritage; speaking another language; and being born in another country.

Try as he does to participate in and observe the life of migrant farmworkers, and experience it as they do, Holmes finds himself in the quandary of being white, tall and bald-headed; of having a different body, and so, navigating the world differently.

For Holmes, the question "Is it worth risking your life?” is a matter of choice, but for his fellow travelers, the decisions to cross the border, toil for low wages, and endure lifelong injury are seen as necessities. This life is full of risks—risks that are based on and compounded by social and economic disparity; risks that are distributed differently; risks that are felt and embodied.

Department

- Anthropology

Article Type

- New Book

Add a Comment